➕ Table of Contents

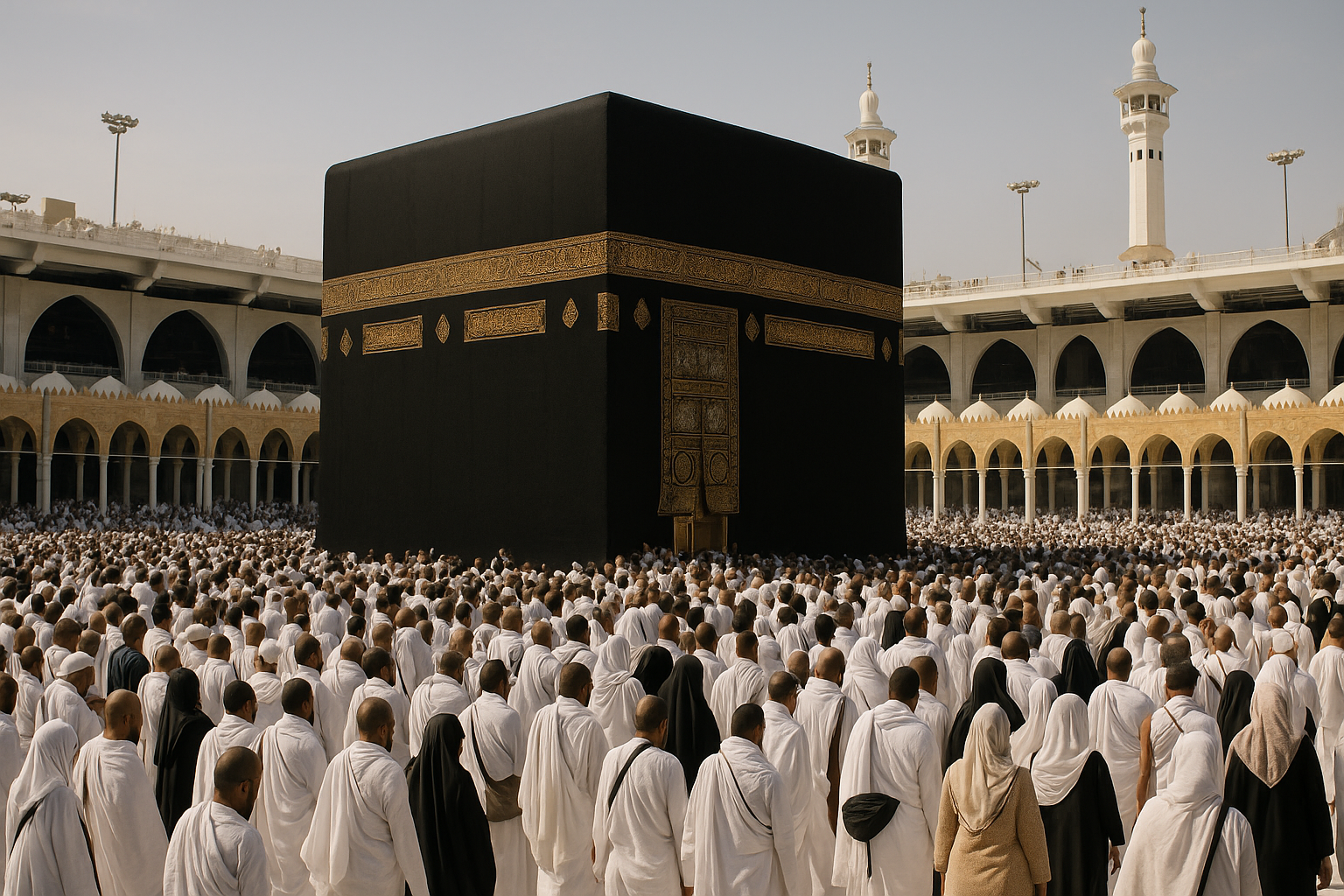

Islam, as one of the world’s largest and most dynamic religious traditions, encompasses a wide spectrum of theological interpretations, legal schools, and spiritual movements. While the profession of faith (shahāda)—affirming the oneness of God and the prophetic role of Muhammad—serves as a unifying declaration among Muslims, the historical development of Islam has given rise to significant internal differentiation. These distinctions, emerging from early disputes over authority, revelation, and religious practice, have shaped not only Muslim identity but also the sociopolitical and cultural landscapes of diverse regions across centuries.

For Christian scholars and theologians, understanding the internal diversity of Islam is of particular importance. Such knowledge facilitates a more accurate engagement with Muslim thought and provides essential context for interfaith dialogue, comparative theology, and missiological reflection. Islam cannot be understood as a single, monolithic entity; rather, it represents a constellation of interpretations bound together by a shared belief in divine revelation and prophetic guidance.

The Early Split: Sunni and Shia

The most consequential division within Islam arose in the earliest phase of its history, immediately after the Prophet Muhammad’s death. What began as a question of political leadership soon developed into a lasting theological and spiritual rift that continues to shape Muslim identity today. The following section explores the origins and implications of this early split, outlining how differing conceptions of authority and succession led to the emergence of Sunni and Shia Islam as distinct traditions within the broader Islamic world.

The Historical Context

The earliest and most enduring division within Islam emerged from a dispute over legitimate leadership following the death of the Prophet Muhammad in 632 CE. The question was not merely political but theological: who possessed the divinely sanctioned authority to guide the Muslim community (ummah) in the absence of the Prophet?

A majority of Muslims accepted Abu Bakr, one of Muhammad’s closest companions, as the first caliph (successor). Others maintained that leadership should have passed to Ali ibn Abi Talib, the Prophet’s cousin and son-in-law, believing that spiritual authority was inseparable from familial connection to Muhammad. This early disagreement crystallized into two enduring traditions: Sunni Islam, centered on communal consensus, and Shia Islam, centered on hereditary spiritual leadership.

The conflict between the two groups deepened through a series of political struggles, most notably the martyrdom of Ali’s son Husayn at Karbala in 680 CE—a tragedy that came to define Shia consciousness and theology. Over time, each branch developed distinct theological frameworks, legal schools, and ritual practices that continue to shape Muslim identity today.

Sunni Islam

Sunni Islam constitutes approximately 85–90 percent of the global Muslim population. The term “Sunni” derives from ahl al-sunnah—“the people of the prophetic tradition”—reflecting their emphasis on following the sunnah (example) of Muhammad as preserved in the hadith literature. For Sunnis, the legitimacy of leadership rests upon communal consensus (ijmāʿ), and the caliph functions as a political, not prophetic, figure.

Sunni theology privileges the collective wisdom of the community in interpreting revelation. Four major schools of jurisprudence (madhāhib)—Hanafi, Maliki, Shafi‘i, and Hanbali—systematized Islamic law (sharī‘a) between the eighth and tenth centuries. While differing in method, these schools agree on the centrality of the Qur’an, the hadith, analogy (qiyās), and consensus as sources of legal reasoning.

From a Christian analytical standpoint, Sunni Islam presents an interesting parallel to the historical role of the Church in defining orthodoxy through communal discernment, though the Sunni understanding lacks any concept of revelation through the Incarnation or the operation of the Holy Spirit within the Church. Its emphasis remains juridical and communal rather than sacramental or Christological.

Shia Islam

Shia Islam—from shī‘atu ʿAlī, meaning “the party of Ali”—emerged around the conviction that authority in the Muslim community must remain within the Prophet’s family, specifically through the line of Ali and his descendants. For the Shia, legitimate leadership is vested in the Imamate: a succession of divinely guided leaders (imams) who possess both spiritual and temporal authority.

The largest Shia group, the Twelvers (Ithnā ʿAshariyyah), recognizes a lineage of twelve imams, the last of whom—the “Hidden Imam”—is believed to remain in occultation and will return as the Mahdi, a messianic figure who will establish justice on earth. Other Shia sub-branches include the Ismailis, who split over the succession after the sixth imam, and the Zaidis, who maintain a less rigid doctrine of hereditary leadership.

Shia piety emphasizes devotion to the imams, martyrdom, and suffering for righteousness. Rituals such as the commemoration of Ashura, marking Husayn’s death, serve as profound expressions of collective memory and identity. In theological contrast to Sunni Islam, Shia thought introduces a more hierarchical and esoteric view of divine guidance, paralleling—at least structurally—the Christian idea of apostolic succession, though without its Christological foundation or sacramental meaning.

Smaller and Reform Movements

Beyond the two dominant traditions of Sunni and Shia Islam, a range of smaller and reformist movements have arisen throughout history, reflecting the dynamic and adaptive nature of the Islamic world. Some developed in the early centuries as alternative interpretations of authority and law, while others appeared in response to modern challenges such as colonialism, secularism, and globalization. Although differing in origin and emphasis, these movements share the aspiration to renew Islamic faith and practice in changing historical contexts. Examining them offers valuable insight into Islam’s theological diversity and its capacity for internal reform—an aspect that, from a Christian perspective, illustrates both the resilience of monotheistic conviction and the limits of doctrinal flexibility without an incarnational center of revelation.

Ibadi Islam

Alongside the dominant Sunni and Shia branches stands Ibadi Islam, a distinct tradition with early historical roots. Emerging from the first century of the Islamic era, the Ibadi community originated among the Khawarij, an early movement dissatisfied with both Sunni and Shia claims to legitimate leadership. Over time, however, Ibadi Islam evolved into a moderate and stable tradition, distancing itself from the radicalism of its origins.

Ibadis emphasize piety, justice, and communal consensus in leadership selection, maintaining that any morally upright Muslim can serve as imam, regardless of lineage. Their jurisprudence developed independently, blending elements of rational interpretation and textual fidelity. Today, Ibadi Islam represents the majority faith in Oman, with smaller communities in North and East Africa.

For Christian observers, the Ibadi approach provides an example of ethical monotheism unanchored from dynastic or clerical hierarchy—an emphasis on virtue and community cohesion rather than dogmatic exclusivity. It stands as a reminder that Islamic identity, even in its earliest centuries, was not monolithic but theologically and politically diverse.

Sufism (Islamic Mysticism)

Sufism represents the mystical and spiritual dimension of Islam rather than a separate sect. Rooted in the Qur’anic emphasis on divine nearness and love, Sufism seeks to cultivate inner purity and experiential knowledge of God (ma‘rifa). Its practitioners, often organized into orders (ṭarīqas), follow spiritual masters (shaykhs) who guide disciples through disciplines of remembrance, meditation, and ascetic practice.

Sufi literature and poetry—embodied in figures such as Rumi, al-Ghazali, and Ibn Arabi—express a profound longing for union with the divine. While some expressions of Sufism employ symbolic or emotional language reminiscent of Christian mystics like St. John of the Cross or St. Teresa of Ávila, the theological basis differs. For the Sufi, union with God does not imply participation in the divine nature, as in Christian theology, but rather the annihilation of the self in God’s will (fanā’).

In Islamic history, Sufism served as a major force for spiritual renewal and missionary expansion, transmitting Islam to Africa, Central Asia, and parts of South Asia. Its emphasis on inner devotion over formal legalism continues to attract followers, though reformist groups often criticize it as a deviation from original Islamic practice.

Modern Reform Movements

From the eighteenth century onward, Islam faced growing encounters with modernity, colonialism, and globalization. These pressures produced diverse reform movements seeking to restore or reinterpret the faith. Some pursued a puritanical revival, while others aimed for intellectual adaptation to the modern world.

The most influential revivalist current, Wahhabism—later known as Salafism—arose in the Arabian Peninsula under Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab (1703–1792). Advocating a strict monotheism (tawḥīd) and rejection of perceived innovations (bid‘a), this movement emphasized literal adherence to the Qur’an and hadith. Supported by political alliances, it profoundly shaped modern Islamic orthodoxy, particularly through its institutionalization in Saudi Arabia.

In contrast, movements such as the Ahmadiyya, founded by Mirza Ghulam Ahmad in nineteenth-century India, sought a rational and reformist reinterpretation of Islam, affirming ongoing divine guidance beyond Muhammad. This claim led most Muslim authorities to declare the Ahmadiyya heretical. Similarly, the Nation of Islam in the United States developed as an Afro-American religious movement combining elements of Islamic symbolism, social justice, and racial uplift; over time, parts of the movement integrated into mainstream Sunni Islam.

From a Christian academic viewpoint, these reformist trajectories reveal how Islam, like Christianity, continually reinterprets its foundational sources in response to historical and cultural change. Yet while Christian reformations often return to the Incarnate Word as the measure of renewal, Islamic reform tends to return to the text and the community as the ultimate sources of authority.

Comparative Overview of Islamic Branches

The internal diversity of Islam can be better understood by summarizing the principal characteristics of its main branches. Though united by a common confession of monotheism and reverence for the Qur’an, these traditions differ in their approaches to authority, interpretation, and spirituality.

| Branch | Leadership Principle | Key Texts / Schools | Major Regions | Distinguishing Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sunni | Community consensus (ijmāʿ); Caliph as political head | Four legal schools: Hanafi, Maliki, Shafi‘i, Hanbali | Middle East, North Africa, South & Southeast Asia | Emphasis on unity of the ummah and legal orthodoxy |

| Shia | Lineage of divinely guided Imams | Ja‘fari jurisprudence; writings of Shia scholars | Iran, Iraq, Lebanon, Bahrain, parts of South Asia | Doctrine of Imamate; veneration of the Prophet’s family |

| Ibadi | Election by merit and moral integrity | Ibadi fiqh and theological commentaries | Oman, Zanzibar, parts of North Africa | Moderate interpretation; focus on justice and tolerance |

| Sufi | Spiritual mentorship under shaykhs | Mystical treatises, devotional poetry | Global | Emphasis on love, spiritual purification, and inner experience |

| Salafi / Wahhabi | Return to early community practices | Qur’an and hadith interpreted literally | Arabian Peninsula, North Africa | Literalism; rejection of innovation; scriptural purism |

| Ahmadiyya | Prophetic reformer (Mirza Ghulam Ahmad) | Qur’an and founder’s writings | South Asia, Africa, diaspora | Modernist reinterpretation; belief in continuing revelation |

While all share the foundational Islamic confession (shahāda), each expresses a distinct understanding of how divine will is to be known and enacted. The differences are not only legal or cultural but reflect contrasting theological assumptions about God’s guidance, revelation, and human authority—questions that also lie at the heart of Christian theology.

Shared Beliefs and Common Ground

Despite their internal differences, Muslims across all branches affirm a coherent set of doctrines that define the essence of Islam. Central among these are the oneness of God (tawḥīd), the prophethood of Muhammad, and the conviction that divine revelation was given in its final form through the Qur’an. These shared beliefs provide unity to the Muslim world and establish a framework for moral, spiritual, and social order.

From a Christian academic perspective, these shared elements offer both points of contact and points of divergence. Islam’s affirmation of one transcendent God resonates with the Christian confession of monotheism, yet differs fundamentally in its rejection of the Trinity and the Incarnation. The Qur’anic concept of revelation as a dictated text stands in contrast to the Christian understanding of the Word made flesh (John 1:14), in which divine truth is revealed not merely through speech but through the person of Christ Himself.

Nevertheless, Christians and Muslims share many moral and ethical values—compassion, justice, prayer, almsgiving, and fidelity to God’s commandments. These commonalities form a foundation for mutual respect and dialogue, provided that both traditions maintain theological clarity. Recognizing Islam’s internal diversity and its shared affirmations enables Christians to engage not with a stereotype, but with the complex and living reality of the Muslim faith.

Contemporary Relevance

In the modern era, the diversity within Islam has taken on renewed significance. The political transformations of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries—decolonization, globalization, and the rise of transnational communication—have re-shaped how Islamic identities are expressed and negotiated. Sunni and Shia distinctions remain central to geopolitical developments in the Middle East, while Sufi spirituality and reformist movements continue to influence cultural and intellectual life across the Muslim world.

From an academic Christian perspective, understanding these dynamics is essential for several reasons. First, Islam’s internal pluralism challenges oversimplified portrayals of “the Muslim world,” revealing instead a mosaic of interpretations, authorities, and traditions. Second, the encounter between Christianity and Islam today increasingly takes place through migration, interreligious dialogue, and shared civic life. Effective Christian engagement—whether theological, pastoral, or diplomatic—depends on awareness of these intra-Islamic differences.

Furthermore, modern reform movements highlight Islam’s ongoing negotiation between tradition and modernity—a tension not unfamiliar to Christianity. Yet, while Christian renewal historically orients itself toward the person of Christ and the Incarnation, Islamic reform typically returns to its textual sources: the Qur’an and the example of the Prophet. Recognizing this distinction clarifies why dialogue between the two faiths must address not only ethics and society but also the very nature of revelation and divine self-disclosure.

Toward an Informed Christian Understanding of Islam

The multiplicity of Islamic expressions—Sunni, Shia, Ibadi, Sufi, and the many reformist currents—illustrates a faith that is both historically grounded and theologically dynamic. For Christian scholars, grasping this diversity provides not only factual understanding but also an interpretive framework for engaging Islam as a living, evolving tradition.

While profound theological differences separate Islam and Christianity—most notably concerning the Trinity, the Incarnation, and the means of salvation—knowledge of Islam’s internal landscape fosters empathy, precision, and informed dialogue. As the Apostle Peter exhorted believers to give an answer “with gentleness and respect” (1 Peter 3:15), so too must Christian scholarship approach Islam with intellectual honesty and spiritual charity.

To understand the types of Islam, therefore, is not merely to classify religious movements but to recognize the varied ways in which humanity seeks to respond to the divine. For Christians, such understanding becomes a foundation for authentic witness—one grounded in truth, humility, and love.

DE

DE  RU

RU  UK

UK