My topic today is the Pope of Rome and the Patriarch in Jerusalem: future possibilities.

Let me begin with a fundamental question: What is the purpose of the Church? What is the unique and distinctive role of Christ’s Church? What can the Church do that no one and nothing else can accomplish? What distinguishes a local church from an ethnic or cultural association, a senior center, or a youth club? What human needs does a priest fulfill that neither a social worker nor a psychotherapist—even with the best training—can meet?

One possible answer is that the Church exists to proclaim the Good News of the Gospel, to deliver the message of salvation in Christ, and to witness to the Kingdom. But we should take this answer a step further. The Church does not merely "proclaim," "deliver," or "witness"; it makes all these things—the Gospel, salvation in Christ, and the Kingdom—tangible and alive. It embodies salvation not just through words but through action. So, what is the fundamental action of the Church? This is, of course, the celebration of the Eucharist, the Divine Liturgy. At the Last Supper, Christ did not call the apostles to "say something" but instead commanded them to "do this." God gave us an action, not just words. Thus, the primary and unique mission of the Church lies in celebrating the Eucharist. The Church is a eucharistic organism, realized in space and time through the offering of the Divine Liturgy. When the Church celebrates the Liturgy, and only then, the Church becomes truly itself. The Church performs the Eucharist, and the Eucharist constitutes the Church. Naturally, the Church has other missions: social, educational, philanthropic, caregiving, and supporting the sick and elderly. However, all other functions of the Church derive their source from the Eucharist.

Thus, the unity of the Church is created by the Eucharist. The Church is not built externally through directives but internally—through the communion of the Body and Blood of God. This becomes evident in the words of St. Paul in 1 Corinthians 10:16-17, one of the most significant texts in the New Testament: “The bread which we break, is it not the communion of the Body of Christ? For we, being many, are one bread and one body, for we all partake of that one bread.” Notice how St. Paul uses the phrase "for" or "because": the one bread of Holy Communion and the unity of the Church do not merely exist in parallel; there is a causal connection between them. Because we all partake of the one bread in Communion, we belong to the one Church. It is this that creates our membership in the one Church and forms our unity in Christ.

Consider the climactic moment of the Divine Liturgy, during the epiclesis or prayer to the Holy Spirit. There is a dual invocation: we ask God the Father to send His Holy Spirit upon us and—simultaneously—upon the gifts set forth. We call upon the Holy Spirit for both the people of God and the elements of bread and wine. Often, we assume that this invocation applies only to the bread and wine, but it is also an invocation of the Spirit upon the people of God. Therefore, when we invoke the Spirit upon God’s people and upon the elements of the Eucharist, everything is sanctified together so that each in its own way manifests the Body and Blood of Christ.

Now, if all of this is true—if the Church is fundamentally a eucharistic organism, if the communion of the Body and Blood of Christ creates the Church—should we not be profoundly shaken, even outraged, by the fact that Orthodox and Catholics remain divided at the Divine Table, that we do not receive Communion together?

The division of Christians, of course, complicates our common work in the world, hinders our missionary efforts, and, naturally, is a tremendous waste of human resources. However, this is not the primary reason why we must overcome the division of Christians. The real reason the division of Christians creates such a deep wound in the Body of Christ lies elsewhere. Because the fundamental nature of the Church is as a eucharistic organism, division contradicts the very purpose of the Eucharist—to make us one body. This is why Christ, establishing the Eucharist at the Last Supper on the eve of His sacrificial death on the Cross, prayed with special intensity for unity among His disciples: “That they may all be one.”

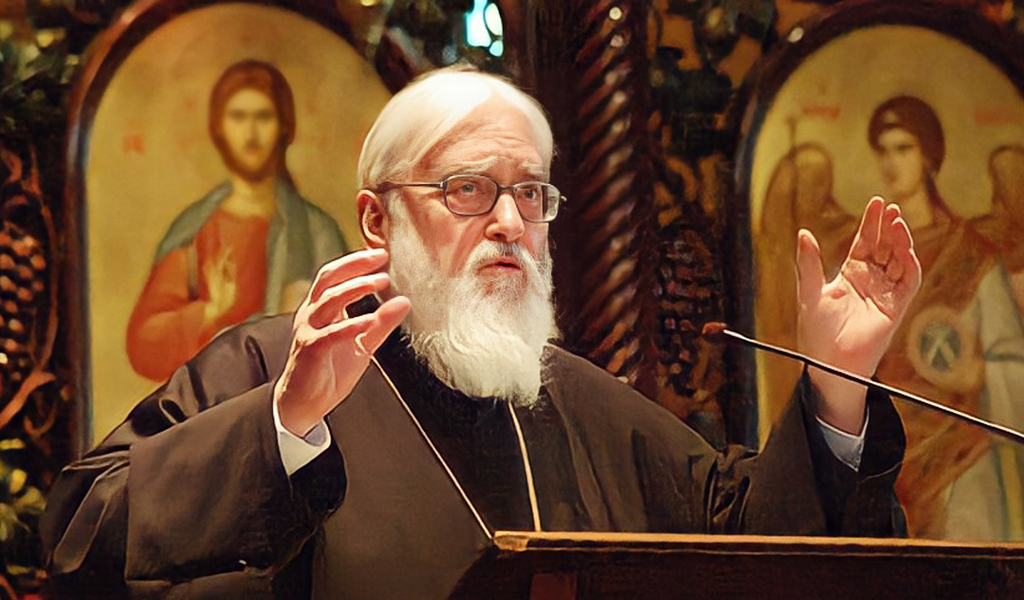

Not long ago, an Orthodox woman asked me, referring to my modest efforts in this area: “Why do you spend time talking to other Christians? Why even discuss the division of Christians and the need for reunion?” My answer to this question is perfectly clear. I am concerned with Christian unity because I believe in the one holy eucharistic Church, because unity is the will of the Savior. I recall the words of Patriarch Athenagoras, who first served as Archbishop here in America and then, from 1948 to 1972, as Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople. Some of you may have known him: a very tall man, and when he embraced you, your face would end up right in the middle of his long white beard. Patriarch Athenagoras used to say that unity is our supreme necessity, our destiny, and our task. Let us not forget his words.

This brings me to the topic of today’s discussion: the recent meeting between Pope Francis and Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew and its potential implications. Why is this meeting significant? We must understand that the Orthodox and Catholic communities share more with each other than with any other Christian tradition. Orthodox and Catholics have so much in common—not only faith in the Trinity and the Incarnation, not only in salvation through Christ, crucified and risen from the dead… We also believe in the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist, that the consecrated elements become the true Body and Blood of Christ. We share a profound love for the Holy Mother of God, a common view of the communion of saints, and a shared reliance on their intercession. We pray for the departed and ask the saints to pray for us. We particularly affirm the unity of the living and the departed in the one Church on earth and in Heaven.

If we share so much, should we not strive together for a closer, visible unity?

The great Catholic pastor, Cardinal Suenens, once said that in order to unite, we must first love one another, and to love one another, we must first get to know one another. For love to be genuine, it must be based on truth; otherwise, it is merely a fleeting sentimental infatuation. Our first task is to identify the truth that exists within our church communities. Without mutual understanding and personal contact, progress toward unity is impossible. This is why the meeting between Pope Francis and Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew is so significant, and why we should take an interest in this meeting and hope for its practical outcomes. The meeting between the Pope of Rome and the Patriarch marked an important step in the process of growing mutual trust. Yes, it was primarily a symbolic event, and of course, it does not resolve all complexities on its own. However, symbols are important and possess great power.

The meeting between Pope Francis and Patriarch Bartholomew in Jerusalem in the spring of 2014 marked the anniversary of an event that took place fifty years earlier. On January 5, 1964, Pope Paul VI and Ecumenical Patriarch Athenagoras met at the highest level for the first time since the Council of Florence in 1438–39. Five centuries of silence were finally overcome. At this year’s meeting, Patriarch Bartholomew remarked, “Pope Paul VI and Patriarch Athenagoras managed to exchange fear for love. We continue their heroic initiative.” A direct consequence of the 1964 meeting was that on December 7 of the following year, the anathemas of 1054 were formally revoked in parallel ceremonies in Rome and Constantinople. You may recall that in 1054, Cardinal Humbert, a papal delegate, entered the Church of Hagia Sophia in Constantinople and placed a scroll of excommunication against Ecumenical Patriarch Michael Cerularius on the holy altar. In response, the Patriarch excommunicated Cardinal Humbert and all his followers. This mutual exchange of anathemas is widely recognized as the beginning of the Great Schism between Orthodoxy and Rome. Of course, the schism was not caused solely by this event but was part of a gradual process that unfolded over centuries. Its roots go much deeper than 1054, and for many centuries after that, Eucharistic communion between Catholics and Orthodox still existed in various regions. For instance, on the Greek islands in the 17th century, regular sacramental intercommunion between the two traditions persisted. Nevertheless, even if the exchange of anathemas in 1054 was not the sole cause or defining event of the East-West split, it was undoubtedly a tragic occurrence. The mutual revocation of these anathemas helped to heal the painful memory of this event.

However, the lifting of the anathemas alone did not restore mutual Eucharistic communion between the Churches. Much later, in 1980, an international commission for dialogue between the Catholic and Orthodox Churches was established. This commission continues its work today, developing documents aimed at fostering reconciliation. We may ask: what consequences should we expect following this year’s meeting? The 1964 meeting sparked unprecedented excitement in our churches and was a genuine breakthrough. The recent meeting between the Pope and the Patriarch did not have the same dramatic effect, as there have been numerous high-level meetings over the past fifty years. Nevertheless, it remains a significant event. Incidentally, I would like to recommend a small book to you—Dialogue of Love: Breaking the Silence of Centuries by John Chryssavgis, which includes an article by Father Georges Florovsky. It is a very useful little book, though unfortunately quite expensive, priced at $25 for only 75 small pages. However, since I am recommending it to you, you might as well "steal" it somewhere.

Returning to the 2014 meeting, one immediate outcome was that on June 8, 2014, Pope Francis invited to the Vatican—his “home,” as he called it—the President of Palestine, Mahmoud Abbas, and the President of Israel, Shimon Peres, along with Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew. They accepted the invitation and met to pray with the Pope for the resolution of the conflict in the Middle East. They planted a tree, and I pray that this tree will grow and bear fruit in a spiritual sense. Pope Francis rightly pointed out that the conflict in the Holy Land can only be resolved if fear no longer dominates us. He added, “True courage is required, and I hope this meeting marks the beginning of a new path.” How many divisions—both ecclesial and political—are caused by fear! Remember that Christ says to all of us: “Do not be afraid.”

Another possible outcome is that Orthodox and Catholics may reach an agreement on a common date for celebrating Easter. This year, Easter fell on the same day, but this is not a frequent occurrence and is unlikely to happen again in the next 20–30 years. Additionally, the Patriarch and the Pope agreed to begin planning for the celebration of the First Ecumenical Council, held in Nicaea in 325. A new ecumenical gathering of Catholics and Orthodox is to take place in the same historic location, now in modern-day Turkey, in 2025.

In Jerusalem, the Pope and the Patriarch clearly articulated the goal of dialogue between our two Churches. They used the term "full eucharistic communion," which signifies unity in the sacraments and all aspects of Christian life. They also emphasized that unity can exist within permissible diversity. Christian unity does not mean uniformity. In a reunited Christian Church, there can be room for various forms of worship, different currents of theological thought, and multiple models of Church governance. We do not need to agree on every detail. What we need to achieve is agreement in faith. And faith is not the same as theological opinions. Let us recall the words of St. Vincent of Lérins, who wrote in the 5th century: "In essentials, unity; in non-essentials, diversity; in all things, charity."

Pope Francis particularly emphasized that every time we abandon our prejudices and find the courage to build new human relationships, we confess that Christ is truly risen. What truly inspires our striving for unity is faith in the Resurrection. In their joint statement, Francis and Bartholomew declared: "God teaches us to see one another as members of one family." The hierarchs rejected what might be called a "minimalist" approach to Christian unity. According to their statement, theological dialogue is not about finding a theological minimum on which we can compromise but rather about seeking the fullness of truth that Christ entrusted to His Church. We should aim for the maximum, not the minimum. We should unite in fullness, in the greatest richness of our authentic traditions. Yes, this is difficult, but through the Holy Spirit, all things are possible.

There were other significant points in their joint statement. The leaders placed special emphasis on the sanctity of the family, rooted in marriage. They also spoke about humanity's responsibility for nature and the Christian response to the ecological crisis, which we often mislabel as an environmental crisis. The problem is not the environment, and what needs to be repaired is not the world outside humanity but the world within us. The ecological crisis is, above all, a spiritual crisis, a crisis of the human heart. The Pope and the Patriarch also expressed their commitment to peace, stating that issues are resolved not through weapons but through dialogue, forgiveness, and reconciliation—these are the only possible means of achieving peace. This applies equally to conflict zones such as Iraq, Syria, Palestine, and Ukraine.

If Catholics and Orthodox share so much in common, what are the main obstacles to our unity? A bit of historical context: the last time we met at the highest level, during the Council of Florence in 1438–39, ten months were devoted to discussing the procession of the Holy Spirit and the addition of the Filioque clause to the Nicene Creed. About four months were spent on the topics of purgatory and the blessedness of the saints. As for the question of papal supremacy, it was given only ten days—and that near the end of the council. Ten months on the Filioque, ten days on papal primacy! Such were the priorities of the 15th century. Our approach in the 21st century is quite different.

In the eyes of most Orthodox and Catholics today, the primary difficulty in the relationship between our Churches is not the theology of the Holy Spirit, though there may still be questions to discuss in this area. No, the chief concern is the position of the Bishop of Rome within the hierarchy of Churches. As Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew put it: "We have different structures for our Churches, and the role of the Bishop of Rome within the framework of the universal Church of Christ remains the principal obstacle for us."

So, the main issue between our two Churches lies precisely in the primacy of the Pope of Rome. While the question of papal infallibility also remains, it does not seem to me to be as complex. We discussed the claims of papal primacy during the last major session of the Orthodox-Catholic dialogue, in which I participated, held in Ravenna in 2007. Unfortunately, the Russian Church was not represented at this meeting and did not accept the agreed-upon statement that was signed there. Incidentally, one curious aspect of the meeting in Ravenna was the heavy presence of police. Italian officers were stationed outside our hotel, along the road to the meeting venue, and even more were present at the venue itself. I could not understand why there was such a significant police presence. Was it to protect the delegates from the residents of Ravenna? Or perhaps to protect the residents of Ravenna from the delegates? Or maybe to prevent a brawl among the members of the delegations? However, when we met the following year in Cyprus, there were no police officers, but we were greeted outside our hotel by a demonstration of Orthodox zealots holding banners with slogans like “No to Unity,” “The Pope is the Antichrist,” and other such reconciliatory messages.

At Ravenna, the joint committee was able to address the central issue I mentioned—the relationship between conciliarity and the primacy of one bishop, the Pope of Rome. The agreed statement from Ravenna unequivocally declares that the fact of the Pope’s primacy at the universal level is recognized equally by both East and West. However, the Ravenna statement does not stop there—it adds an important nuance. While both sides agree that the Pope of Rome is entrusted with the supreme duty of universal service for the entire Christian world, we have yet to thoroughly examine how this right to universal service, this primacy, can be interpreted and what it truly means. This task was left by the Ravenna meeting to subsequent councils of Orthodox and Catholic theologians. But the key takeaway remains the acknowledgment of the fact of universal primacy in the Pope’s ministry. This, in itself, was a significant statement, as some Orthodox Christians have denied this fact for centuries, and the Russian Church continues to deny it to this day.

The Ravenna statement emphasizes that even in the first millennium, when the East and West were in full eucharistic communion, there were different ways of interpreting what Roman primacy meant in various regions. Even during that time of eucharistic unity, no clear consensus existed on this question. Therefore, we must ask today: what are the boundaries of permissible diversity? How can different understandings of papal primacy coexist within the Church without disrupting its unity? This is precisely what we are currently engaged in through the dialogue: a detailed exploration of the question of the primacy of the Pope of Rome. It must be said, however, that progress on this issue is very gradual.

Shakespeare’s words from A Midsummer Night’s Dream come to mind:

"The course of true love never did run smooth."

I fear these words equally apply to our Orthodox-Catholic dialogue. Nevertheless, we continue our efforts.

Nevertheless, allow me to propose a possible Orthodox approach to the question of papal primacy. We could view it as a primacy of humility, service, and love. However, we should avoid speaking of it as an abstract supremacy. Instead, should Orthodox Christians not consider that the Pope of Rome is endowed with a unique pastoral mission and an all-encompassing pastoral care? His role is not limited to a primacy of honor, something ceremonial or formal; he does not merely hold nominal authority—and history provides many examples of this. His ministry embodies entirely different qualities: he oversees the well-being of the Church, its peace, and unity. Is it not his responsibility to intervene in situations where peace and unity are threatened anywhere in the Church? Of course, he would not impose his decisions artificially from above, but rather, he should activate initiatives that promote reconciliation.

Orthodox Christians are certainly not prepared to acknowledge the Pope of Rome's direct legal authority, at least concerning the Christian East, as demanded by the First Vatican Council. However, we may believe, as St. Ignatius of Antioch wrote just 60–70 years after the death of Christ, that “Rome is the Church which presides in love.” It is precisely in this light that we can view the ministry entrusted to the Pope of Rome.

There are two papal titles that we should take to heart. One of these titles is “The Caretaker of All the Churches.” These words describe the ministry of St. Paul himself (2 Corinthians 11:28), and Popes of Rome have used this title since the 4th or 5th century. The other title is “Servant of the Servants of God,” a designation that has been in use since the time of Pope Gregory the Great in the late 6th century.

I began my speech with a quote from Patriarch Athenagoras, who said that “unity is our necessity.” But let me end with another quote from Patriarch Athenagoras: “Unity will be a miracle, but a miracle within history.” Let each of us personally do everything we can to overcome the human obstacles standing in the way of this miracle.

DE

DE  RU

RU  UK

UK