➕ Table of Contents

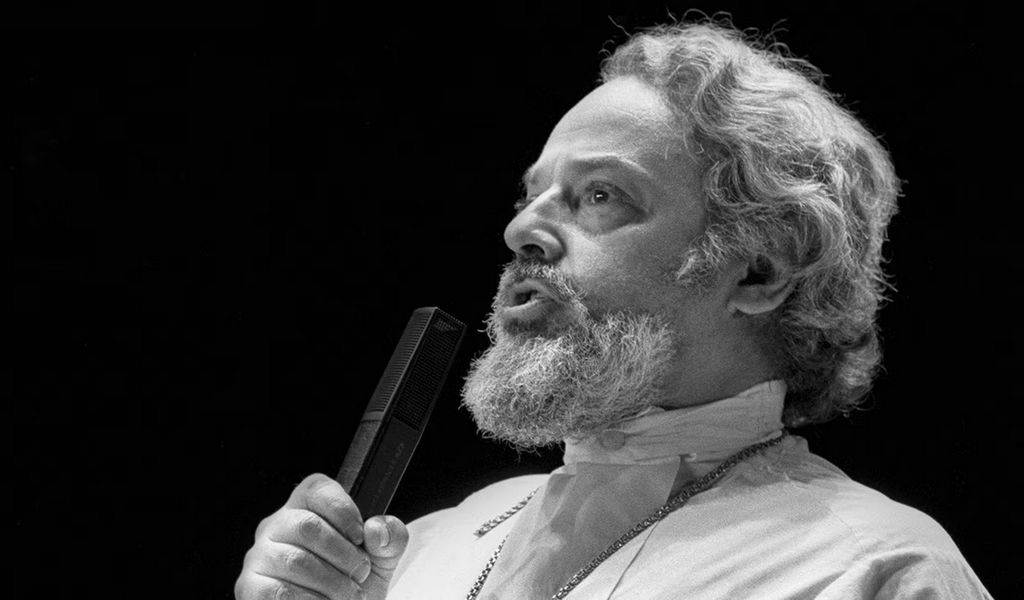

In a lecture on Judeo-Christianity delivered to an audience of Jews, Father Alexander Men explains the Christian faith using terms that are familiar within the framework of Judaism.

Friends! I have been asked to share some thoughts, events, names, and my reflections on the question: what is Judeo-Christianity? Does such a phenomenon even exist, or is it a myth? My entire life has revolved around this topic, both in thought and in action. Please forgive me if anything I say comes across as clumsy or insufficiently substantiated.

I am afraid that Judeo-Christianity, as a distinct entity, does not exist today—it is a myth. What exists is Christianity among Jews, just as there is Christianity among Russians, English, or Japanese. The term "Judeo-Christianity" implies a synthesis between Old Testament practices and New Testament faith. For now, such a synthesis does not exist anywhere. However, I must say, looking back into history, that it once did: there was a unique Judeo-Christian Church that existed for about five centuries at the beginning of our era.

A brief preamble: religious questions are often confused with national ones. Recently, in the Israeli newspaper Menorah, a certain Barsela wrote with great fervor that Jewish Christians are trying to poison the national consciousness of Israelis, attempting to implant the heresy of Christ into their minds. For him, a Jew who adopts another faith becomes a traitor to their people. Of course, for me, this kind of incendiary rhetoric represents a national form of black-hundredism, as it lacks reasoned arguments or logic—only emotions. The origins of these emotions are clear: a conflict pattern between Jews and Christians that has been shaped over millennia. Centuries of antisemitism and, conversely, disdain for gentiles have fueled mutual hatred.

Today, we have two choices: we can either continue to relive this hatred (which is easier), or we can try to rise above it—as human beings, as Israelis, or as members of any nationality.

Thus, the assertion that in our time, in the 20th century, one can speak of an automatic equivalence between nations and religions seems absurd to me. If a person is non-religious, such as Trotsky or Kaganovich, they are still Jewish. If someone is an occultist or a theosophist, a follower of Steiner, and they are Jewish—they have adopted another faith, but they remain Jewish. Was Spinoza, excommunicated from the synagogue, not a Jew? All of them were Jewish.

In the ancient world, nation, society, and religion were almost always synonymous. Closed civilizations required this, and this identity partially persisted in later societies. Terms like "Russian" and "Orthodox" were also considered interchangeable. Yet today, we know that a Russian can be a militant atheist, Orthodox, or Baptist and still remain Russian. Leo Tolstoy was quintessentially Russian but was never Orthodox, at least not during his conscious adult life. We now live in an era where life itself inevitably compels us to separate faith from nationality. Statements like Barsela's appear to be relics of the past.

Conversely, I recently encountered the theses of Dr. David Flusser, an expert on the Dead Sea Scrolls (Qumran materials), early Christianity, and the Second Temple period. In these theses, he spoke about the genetic connection between Judaism and Christianity. His perspective, as a professor at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, is rational, calm, and objective. I could agree with all of his points, except those concerning mystical matters. In such areas, there’s no need to argue, but rather to share internal convictions with one another.

Was David Flusser correct in asserting that Judaism and Christianity are one faith, "one face" (as he phrased it)? If he is correct, then the possibility of Judeo-Christianity is evident.

I can answer this question ambiguously: Flusser is both right and wrong. Undoubtedly, Christ embraced everything contained in the Bible and the rabbinic spiritual tradition—the entire heritage of the Old Testament—as something organic and sanctified by Him. Yet to state, as David Flusser did, that Christ was a Jew, lived within Judaism, and died for it, does this not imply something paradoxical? For if that were the case, what new element did Christianity bring? Then Christianity itself would not exist! However, we do see that there is a difference.

So now, I will try to trace where the points of contact lie deep within and where the divergences begin.

First and foremost, I must begin with Christ's words as an epigraph: "Do not think that I came to abolish the Law or the Prophets; I did not come to abolish but to fulfill" (Matthew 5:17). These words are far from being universally understood correctly.

By "the Law" ("Torah"), Christ did not mean the entire conglomerate of ritual prescriptions. He was referring to the concept proposed several centuries before Him by the famous Rabbi Hillel, who said that the essence of the Law and the Prophets lies in moral service to God, with everything else being commentary. For Christ, the Law consisted precisely of this. He considered the two greatest commandments to be "Shema Yisrael" ("Hear, O Israel"—the opening words of the commandment affirming the oneness of God) and the second: "Love your neighbor as yourself." This, for Him, was the essence of the Law.

Moreover, Christ never rejected external ritual practices. Only Tolstoyans, liberal theologians, and rationalist critics believed that He sought to establish a religion devoid of rituals. On the contrary, Jesus Himself participated in rituals. For example, after healing a man, He instructed him to go and show himself to the priest, as required by the Torah. Christ even expanded the number of rituals: He instituted the sacrament of the Eucharist based on the Jewish Passover celebration and established the sacrament of baptism rooted in the Jewish rite of proselyte initiation.

Jesus observed and instituted rituals because He addressed living people of flesh and blood who needed external expressions of their faith. However, when He said that He came "to fulfill the Law," this does not mean He intended to follow all the commandments literally. Many others sought to follow all the commandments. Rabbi Shammai, the counterpart to Hillel, who also lived in the 1st century BCE, strove to observe every commandment, even inventing new ones that were not part of the Oral Torah by deriving them logically from existing ones. Is this what Christ meant? No.

The word used in the original text of this Gospel passage does not mean "fulfill" in the sense of "carry out." The word is plerosis, which means "to complete" or "to bring to fullness," derived from pleroma, meaning "fullness." Christ wanted to emphasize that the teachings of the Old Testament are an open system in need of completion. His teaching—or more accurately, His appearance—was the completion of the Old Testament.

For both the New Testament and the Old Testament, the foundational theological point is the incomprehensibility of God. The Israelite consciousness approached speculative metaphysics with great skepticism. God was recognized as incomprehensible, Kadosh—Holy, entirely Other, beyond human capacity to behold. This was reflected in the prohibition against creating images of God. God could only be symbolically present through Theophany, through His Glory (Kavod), manifest in a cloud, a fiery tongue, or luminous smoke.

Ultimately, all thinkers arrived at the idea of God’s total otherness in relation to the world. This conclusion serves as the highest and final note in human reflection on God. Indeed, as people abandon crude mythological representations and ascend ever higher, they eventually arrive at the concept of a Universal, Pure, Cosmic Mind or Action, Energy, Force—Divinity that defies description. This gives rise to apophatic theology—a theology that holds it is impossible to make any positive assertions about God because He surpasses everything, including existence itself.

Apophatic theology was developed in Indian philosophy, Greek philosophy (especially in Neoplatonism), and among the Christian Church Fathers. In Israel, this was expressed in the concept of Kadosh—the Holiness of God. Yet this God, who infinitely transcends all created reality, was revealed as the Father of the world—a loving Father. This is the extraordinary, astonishing, and transformative revelation of the prophets: that God is deeply invested in the world, that He seeks closeness with the world from which He is distant, and desires to form a covenant (Berit) with it. He seeks to unite the world to Himself, to redeem it—taking it as His possession, drawing it near. This miraculous revelation bridges the Old Testament and the New Testament. How did it occur?

Describing this process rationally is impossible. Before us are individuals, operating in Palestine and the diaspora over several centuries, who spoke on behalf of God and felt His action within themselves so profoundly that they spoke in the first person. They didn’t merely relay God’s words—they seemed to become God: “Come out, My people...” and so forth. Who is speaking—God or the prophet? It is God speaking through the prophet.

There have been many attempts to model this way of thinking, to analytically penetrate the mystery of this dual consciousness. Some progress has been made, but the miracle remains a miracle. In other religions, mystical and ecstatic unions with God are known, where the Divine enters the human. But in all these cases, the human is overwhelmed and dissolved, as illustrated in the well-known parable of the salt statue that sought to know the taste of the sea and dissolved into it.

Here, however, the miracle is different—it is the beginning of a new relationship where the Divine and the human engage without the latter being annihilated. This unique dynamic forms the heart of the Judeo-Christian revelation, leading us from the Old Testament to the New.

The Pythias, soothsayers, seers, Bacchantes, Dionysians, and Maenads—all of them spoke in a state of madness, possession, or frenzy (the word Maenad itself derives from this concept). Prophets, however, not only remained fully themselves, retaining their personal consciousness, but even argued with God. Jeremiah, for instance, resisted preaching what God commanded him to say. He felt sorrow for Jerusalem and his people, yet he declared: "Thus says the Lord... the city will be destroyed, and the Ark will no longer be remembered, for it will no longer exist" (paraphrasing the essence of Jeremiah’s message, as reflected in Jer. 3:16–17: "In those days, declares the Lord, they will no longer say, ‘The Ark of the Covenant of the Lord.’ It will not come to mind, nor will they remember it; it will not be missed or made again. At that time, they will call Jerusalem the Throne of the Lord.” See Jer. 5:17: “They will destroy your fortified cities in which you trust.”).

Jeremiah wept, complained, and told God that he did not want to deliver such a message, but the Word of God burned within him. This phenomenon (if it can even be called a phenomenon—my use of the term is imprecise) of the remarkable closeness of two “selves”—the Divine Supra-Self and the created human self—reveals the deepest essence of Israelite religion.

When Christ, the Son of Man, appears, this phenomenon reaches an absolute level, where the Divine and the human are almost indistinguishable. Here stands a unified Person, not merely a messenger, though Christ often refers to Himself as one. Prophets were consumed by the Word of God, but Christ declares, “I and the Father are one.” Prophets never spoke like this. When Isaiah encountered the vision of God, he said, “Woe to me! I am ruined! For I am a man of unclean lips... and my eyes have seen the King, the Lord Almighty” (Isa. 6:5). Christ, on the other hand, was devoid of any consciousness of sin, saying, “I am the light” (John 8:12).

This is an entirely different kind of consciousness—a Prophet fully united with God, a Prophet in whom human and Divine consciousness merged into one phenomenal Person. Only such a Person could establish a global religion for billions of people spanning many centuries. As most Christians rightly say, the Gospel’s primary gift is not a new doctrine but the highest and greatest union of God with humanity. Christ says, “I am the Way” (John 14:6) and “All things have been committed to Me by My Father” (Matt. 11:27). He reveals God through Himself, for He bears God within Himself in an absolute sense.

At this point, only faith can speak. Why did people follow Him when they saw Him? Was it because He told them, “Love God”? But Hillel, the Prophets, and the Torah said the same. Was it because He spoke of Divine Mercy? So did the prophet Hosea. Was it because He proclaimed the Kingdom of Heaven? But the Kingdom of God was spoken of by Daniel, the apocryphal texts, and all apocalyptic writings. Everyone awaited this Kingdom.

What then drew people to Him—His miracles? Yet Israel had miracle workers. There were also seers: the Essene Menachem foretold Herod’s kingship when Herod was still a boy, and around 100 CE, the Essene Judah attracted many with his remarkable prophecies. Such gifts existed in Israel and likely still do. But none of these individuals founded anything remotely comparable to Christianity.

The unique, phenomenal presence of God in this Man is what created Christianity. When critics of the Gospel claim it contains no doctrine of Christ’s Divine nature, that He was merely a prophet, they strip the Gospel of its plausibility. A Christ preaching a Tolstoyan philosophy could never have accomplished what was done. A character like Christ could not have been invented, even by a genius, and yet the Gospel was written by four individuals.

Still, as all who have objectively read the Gospels attest—even in poor or outdated translations—the power of Christ shines through. Where does this come from? Were all four evangelists geniuses? No. Their light is a reflected light, like the moon reflecting the sun. Such a Person existed.

Moreover, as one contemporary theologian remarked, for us, Jesus is not simply someone who was—He is. He exists not only in memory but actively participates in the divine-human drama, fulfilling the very Covenant prophesied by Jeremiah—a Covenant between God and humanity.

This Covenant, in the consciousness of Israel, was deeply tied to the coming Kingdom. Unlike most ancient religions, which were static systems of rituals, morals, and beliefs, Israelite religion was dynamic. It embodied a hope for the future, a journey initiated by Abraham and continued into an unknown horizon. It was always an anticipation of something monumental to come. “The time will come when the Law will go forth from Zion, and the Word of the Lord from Jerusalem, and all nations will gather, and heaven and earth will tremble. Oh, that You would rend the heavens and come down!”

The prophets foresaw something cosmic, an extraordinary Theophany. Either they were deeply mistaken or blind, or these prophecies found their fulfillment in Christianity. Otherwise, what were the prophets speaking of? The rebirth of Israel as a state? Imagine centuries passing, wars ceasing, and a small state emerging—a coastal nation like many others, with an ordinary parliament, ordinary sins, and ordinary restaurants. Could this possibly compare to what the prophets envisioned—that heaven and earth would shake, that the entire world would be transformed?

The prophet Isaiah, or "Second Isaiah," speaks to Israel as its personification, its servants: “I will make you a light to the nations” (Isa. 49:6). In what sense? When did this happen? It truly did happen—but only once, and never again. Two thousand years ago, the Old Testament was taken, metaphorically speaking, into Christ’s right hand, given to the nations, and they came and worshiped. It was fulfilled.

This occurred despite the nations being as sinful as Israel—just as prone to turning away from God and breaking His will as Israel was in the Old Testament. Yet they stood under this sign, under this banner. In the Old Testament, the coming of a prophet, a king, and a high priest was anticipated. Christ fulfilled all three roles:

- He was a Prophet, in the sense I’ve just described—God acted through Him.

- He was a King, as He is now the Sovereign of the New Life, though it cannot be described in abstract terms.

- Finally, He was the High Priest, the mediator standing between the altar, the people, and Heaven. Christ Himself is the “door,” as He says: “I am the door” (John 10:9)—the open door to Heaven.

Does this contradict Old Testament faith? Not at all. During the time of Hillel, Shammai, and the first Tannaim, it was believed that this world (Olam ha-zeh) would be replaced by the world to come (Olam ha-ba), where everything would be different. They believed God would draw near to humanity and a new era would dawn. The Apostle Paul, often unfairly accused by Jewish writers of diverging from Judaism, wrote entirely within these Jewish categories.

Paul said, “The form of this world is passing away” (1 Cor. 7:31), and Christ spoke of two worlds, two ages, two aeons. Christ proclaimed that with His appearance, the Old world had ended and the history of the New had begun. This teaching did not contradict the hopes of the Pharisees and scribes; indeed, many Pharisees and scribes converted to Christianity.

The Law given by God at Sinai and afterward appealed to human will, conscience, and reason. However, it did not provide humanity with the strength to fulfill its commandments. This is why the Apostle Paul compared it to a fence, and in the Talmud, it is also called a “fence.” In Pirkei Avot (a tractate of the Talmud), it says: “Make a fence around the Law.” The Law primarily served a protective function, creating a boundary around holiness.

With Christ, however, the fence was opened, and the transformative power of grace was revealed.

So, what defines the New World proclaimed by Christ? In this new reality, God interacts directly with humanity, and through this interaction arises the power we call "grace," which enables a person to fulfill God's will. The fulfillment of all Old Testament rituals is no longer necessary. These rituals were protective mechanisms designed to preserve the nation and its faith in the midst of a powerful pagan environment. When the need for protection disappeared, much of the ritual law also became obsolete.

The sacred authors who compiled the Torah’s rules on rituals and prohibitions incorporated archaic concepts, including taboos. Half of the laws in the Torah were borrowed from the ancient Babylonians, Canaanites, and the inhabitants of Phoenicia and Ebla. These borrowings were a means to create a cohesive religious, legal, and ritual framework that would unite and fortify the people, making them a stronghold amid a sea of paganism.

In evolution, protective mechanisms of an organism often become hindrances rather than aids. This has frequently been true in human history as well. The "armor" of the Torah sometimes became so cumbersome that it impeded spiritual development. The Talmud itself warns: "Do not build too high a fence around the Torah, or it will collapse and destroy the plants within." This is a profound warning, and history has shown its relevance many times.

This tendency is not unique to Jewish psychology; ritualism is inherent to human nature. Every civilization gravitates toward rituals that unify life, whether they are Confucian rules or Roman laws. These systems serve a functional purpose. However, systems of law can become self-serving, turning into fetishes that hinder life.

When Christ criticized the scribes and Pharisees, He opposed their abuse of form, not the Sabbath itself. "The Sabbath," He said, "was made for man," meaning it was intended for rest and celebration (Mark 2:27). However, when people turned it into a cult and believed that helping someone in need on the Sabbath was forbidden, this became a caricature of the commandment. Such legalism has been characteristic of all times and peoples.

The Revelation of God in Christ

This brings us back to the central point: Christianity is the revelation of God through the person of Christ. We come to know this revelation through an inner experience based on the Gospel. Does this represent a departure from Jewish monotheism, a betrayal of it, or a "paganization" of Judaism (from paganus—"pagan")? Not at all.

Long before the Christian era, Jewish theology had already developed the idea of hypostases within the Godhead. Concepts such as Ruach Elohim ("Spirit of God"), Hokhma ("Wisdom"), and Memra (the Aramaic term for "Word") all represented aspects of God acting as God Himself. In the earliest layers of the Bible, we encounter expressions like Malach Elohim ("Angel of God"), who is simultaneously identified as God. There is a kind of self-distinction within the Divine, certain faces (panim) within God. This does not imply multiple gods, nor does it reduce Divine Wisdom, the Word of God, and the Spirit of God to mere attributes.

In the Book of Proverbs, for instance, Wisdom speaks of herself as being present at the very act of creation, as a master craftsman. These Divine Theophanies inherently possess a personal aspect—they are hypostasized.

The Fulfillment of Old Testament Faith

When we speak of the action of the Word of God in Christ, we continue, deepen, and develop the Old Testament belief in the mighty action of the Divine Word. When we speak of the Spirit as tongues of fire over the apostles, hovering over Jesus at the Jordan, or being sent by Him to empower the disciples to preach, we are still speaking of the same God—the Ruach who creates the world, raises dry bones to life (Ezek. 37:7), and builds a people.

We deepen the Old Testament faith in Wisdom when, with the Apostle Paul, we confess Christ as the Wisdom of God (1 Cor. 1:24). The term Hokhma (Wisdom) is carried over into the Gospel of John with Logos, a Greek translation and deepening of these Old Testament concepts.

Thus, Trinitarian theology—complex as it may be—has its roots in Old Testament theology and has no connection to polytheism or paganism. It represents the fulfillment and ultimate realization of the faith of Israel in the One God who reveals Himself in manifold ways.

Another matter is that when Christianity entered pagan lands, it inevitably absorbed certain elements of paganism. Similarly, when Jews settled in different countries, they also absorbed elements of the surrounding cultures. One example: archaeologists excavated a Canaanite city and found remnants of sacrificial practices, showing how offerings were made and which parts were given to the priests. It all aligned with the descriptions in the Book of Leviticus. Since the Israelites had only recently arrived, it is evident that they borrowed these practices from the Canaanites. Even the cherubim guarding the Ark of the Covenant are of non-Jewish origin, along with many other elements. Nations and cultures interact—there’s nothing alarming about this unless such interaction becomes destructive.

The early Christians, far from provoking hostility as they sometimes do in modern Israel, were actually beloved by the people, as noted in the Book of Acts. They were admired for their piety, and many Pharisees joined them. Rabbi Gamaliel, the grandson of the great Hillel, was sympathetic to Christians. Much later, a legend arose that he became a secret Christian. In any case, during a trial where the Sadducean Sanhedrin sought to condemn the apostles, Gamaliel defended them, saying, "We do not know if this might be God's doing. We should not persecute them" (paraphrased from Acts 5:34).

When the Apostle Paul was brought before the tribunal, the Pharisees came to his defense after he declared, "Brothers, I am a Pharisee, the son of a Pharisee. I am on trial because of my hope in the resurrection of the dead!" The Pharisees attacked the Sadducees, saying, "This man has done nothing wrong. And if an angel or a spirit has spoken to him, we could be opposing God" (a loose retelling of Acts 23). We also know that the Apostle James, the brother of the Lord, was killed by the Sadducean Sanhedrin. Josephus recounts that this so outraged the Pharisees, who were opposed to the Sanhedrin, that they went to the Romans, demanded the high priest’s removal, and succeeded. This caused considerable unrest, as noted by Josephus.

Moreover, when Gentile Christians began to appear, they regarded Jewish Christians as an elite. Dr. Flusser even suggested that Jews could have become a kind of Brahmin caste within Christianity. While this was possible, it was precisely what needed to be avoided. Jewish Christians themselves often aspired to this elite status, and Gentile Christians were inclined to reinforce it. Even in the fifth and sixth centuries, Greek and Persian Christians, when blessing crops, homes, or performing other sacred acts, would often call upon a Jew, believing that their blessing was more effective.

I do not deny that Jews might carry some mysterious Grace. However, we are a tempestuous and "stiff-necked" people. God chose us for that very reason, for the meek could never have created a global religion. Our pride is already substantial enough; there is no need to further nurture it. On the contrary, healthy humility is far more beneficial than an inflated sense of greatness. It is wrong to humiliate a person, but it is equally unwise to flaunt one’s chosenness. Such behavior comes across as intrusive and unappealing.

Among ourselves, we can discuss this, but modesty never harmed anyone. It is far too easy to become tiresome. We already make quite a loud statement, starting with the Bible and ending (as I will note in passing) with the latest military events.

When the first Gentiles began to convert to Christianity, most Jews protested: “How can they become Christians without accepting the Law of Moses? They must go through circumcision and other requirements.” This became a significant obstacle, as many Greeks and Romans found circumcision completely unacceptable. It’s worth remembering that circumcision was common in Egypt and among Arabs but was entirely unknown in the Western world.

To address this issue, the Apostolic Council was convened in Jerusalem in 51 AD. It was decided that Jewish Christians could continue observing the customs of the Law, but Gentile Christians were exempt from these requirements. The subsequent development of the Church demonstrated that this exemption became a crucial factor in the global spread of Christianity.

Jewish Christians continued living in small, closed communities, reading the Bible in Hebrew (unlike Gentile Christians, who used Greek). These communities observed the Sabbath and retained the original name for Christians, Notzrim ("Nazarenes"), in memory of Jesus of Nazareth (Yehoshua ha-Notzri). They were also called Ebionites ("the poor"). These communities had their own bishops and places of worship. After the Bar Kokhba revolt, when Jews began returning to Judea, relatives of the Lord's brother James settled in Nazareth. They lived there, built small churches, and maintained their way of life.

By the mid-2nd century, Justin Martyr wrote that he knew of such people in Palestine—those who observed the Law and lived as Christians. These communities survived until wars, destruction, and the forced expulsion of Jews from Palestine, followed by the arrival of Arabs, led to their disappearance. Even "ordinary" Jews were largely displaced from these regions.

A Universal Religion

The early Judeo-Christian Church included notable figures such as the apostles James, Jude, and Simon. Early Christian writers tell us a little about this Church, though not much.

Once, I asked a Jew who had recently become religious if he considered Judaism the true religion. My question may have been blunt, but it was deliberate. He replied that Judaism was true for Jews. To this, I countered that truth can only be for everyone or no one—it is either truth or it is falsehood. If two plus two equals four for a Chinese person, it is also true for an Indian.

Thus, there cannot be a special “Jewish religion,” although there can be national religious customs. Some Christians also dismiss the “Jewish God” as foreign. Yet the Church, as St. Justin Martyr declared to Rabbi Tarphon, worships the same God who led Israel out of Egypt with a mighty hand and an outstretched arm.

Judaism's Global Mission

Judaism was designed—yes, I use this word deliberately—by God as a universal religion. This is evident throughout the Bible. It could not remain confined within the borders of Israel. What was developed within the Jewish people was intended for the whole world.

Despite the conflicts and struggles between Judaism and Christianity, the sense of kinship and connection between the two faiths is becoming increasingly clear. Martin Buber called Christ "the central Jew." Dr. David Flusser observed that Jesus is not a Caesar; while He once divided Jews, He now has the potential to unite them. The famous British politician Benjamin Disraeli argued that with the Gospel, the Semitic cultural essence became an inseparable part of Europe. Similarly, the historian of the Church, August Neander (a 19th-century Jewish convert to Christianity), Henri Bergson, and many others shared this perspective.

The Path Forward

Experiments like those of Joseph Rabinowitz and other preachers, attempting to assimilate Jewish groups into Christianity, were inconsistent and ultimately lacked a clear vision. The future resolution of this conflict must take a different form.

Some Jews might come to see Christ as a great teacher and prophet—the greatest from among their people. But for Christians, He is far more than that. For us, His voice is the voice of God, and His face is the face of the Eternal. Nothing more needs to be added—nor could it be. No one else has ever accomplished what He did, nor could any person achieve it.

Faith in Modern Israel

In Israel today, believers constitute a minority. The majority have abandoned any faith and live in spiritual desolation. It would be a good thing if these people were not forced into some official state religion, as was common in the past, but instead were offered the freedom to choose their path.

If they return to Judaism, that is good. If they seek other paths, that is also good. If they come to Christianity, they will not cease to be Jews but will instead be more deeply connected to their tradition. However, this tradition will no longer be confined to an archaic or narrowly national framework. It will become something broad, universal, and powerful—like the very foundation of the Church itself.

Father Alexander Men

Summary Table: The Evolution of Early Christianity and Its Relationship with Judaism

| Topic | Details |

|---|---|

| Acceptance of Gentiles | Jewish Christians initially resisted the inclusion of Gentiles without adherence to Mosaic Law (e.g., circumcision). The Apostolic Council in 51 AD exempted Gentiles, facilitating the spread of Christianity. |

| Jewish Christian Communities | Continued observing the Law, reading the Bible in Hebrew, observing the Sabbath, and maintaining distinct identities (Notzrim, Ebionites). Declined due to wars, displacements, and the Arab conquests. |

| Cultural Interaction | Christianity, like Judaism, absorbed elements from surrounding cultures. Examples include sacrificial practices and cherubim, which were borrowed from Canaanite traditions. |

| Initial Jewish-Christian Relations | Early Christians were respected by many Jews, including Pharisees like Gamaliel, who defended the apostles against persecution. Some Pharisees converted to Christianity. |

| Spread of Christianity | Gentile Christians regarded Jewish Christians as spiritual elites. This dynamic, though influential, was deliberately avoided to prevent divisions. |

| Judaism as a Universal Religion | Judaism, according to the author, was designed by God as a universal faith meant to transcend Israel's borders and reach the world. |

| Theological Connections | Early Christian theology built on Jewish concepts like Ruach Elohim (Spirit of God), Hokhma (Wisdom), and Memra (Word), showing continuity rather than contradiction. |

| Modern Faith in Israel | Most Israelis today are secular. The author advocates for religious freedom, allowing individuals to choose Judaism, Christianity, or other spiritual paths. |

| Key Figures and Views | - Martin Buber called Christ "the central Jew." - Dr. Flusser viewed Christ as a unifying figure for Jews. - Christianity brought the Semitic essence to Europe, as noted by Disraeli and Neander. |

| The Future of Jewish-Christian Relations | The relationship between the two faiths should focus on mutual understanding and integration of shared values while avoiding past conflicts. |

This table encapsulates the key themes and ideas discussed in the article, highlighting the historical and theological interplay between Judaism and Christianity.

DE

DE  RU

RU  UK

UK